The subject of this post, the fossil genus Archimedes, belongs to phylum Bryozoa (bryo, moss; zoon, animal), which has an extensive fossil record. These animals are always colonial, and the colonies range in size from microscopic to, rarely, more than 1 meter across. Bryozoans live (and lived in the past) mainly in marine environments from shallow seas to abyssal depths and from tropical to polar regions.

The fenestrate bryozoa (Ordovician–Triassic) comprise a distinct group within the Bryozoa. They have delicate lattice-like morphology that grew in upright fan-shaped or funnel-like colonies (expansions) cemented to some foreign object by means of a root-like structure, near the base of the colony. Fenestrate bryozoans ate microscopic organic matter that they strained out of the water.

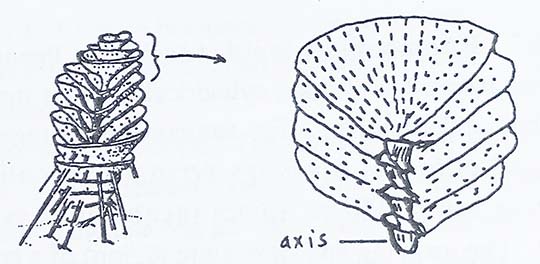

One of the most spectacular fenestrate bryozoan fossils is named Archimedes, which is a Greek name for a screw used to elevate water. Archimedes has a calcified corkscrew-shaped central spiral axis, and branching off from the axis are lattice-like fenestrate fronds. Finding a spiral axis with its branches intact is very rare.

A complete colony of an Archimedes is shown on the left. Also, an enlarged view of some of the fenestrate fronds are shown to the right.

An actual specimen of just the fenestrate fan part (36 mm wide and 40 mm high) of an Archimedes fossil.

The spiral axes (or screws) of Archimedes can have either sinistral (anticlockwise) or dextral (clockwise) coiling direction, and this phenomenon is referred to as “chirality.” Two “screws” shown above are both 33 mm in length. The one on the left is sinistral coiled, whereas the one on the right is dextral coiled.

To the uninitiated, large specimens of just the central spiral axis (like those shown above) of Archimedes can resemble the backbone of an animal. I know this first-hand because one of the first fossils I ever saw was of a large Archimedes collected by one of my relatives, on his farm near St. Louis, Missouri. I thought that it was a backbone, but many years later when I was an undergraduate in college, my historical geology instructor quickly identified it as an Archimedes. Per his request, I donated that specimen to the “Mineralogy and Paleontology Museum” of the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. As far as I know it is still there and still on display.

Archimedes is common in the Paleozoic fossil record, with a geologic range from Carboniferous (Mississippian and Pennsylvanian) to Permian. The Carboniferous age specimens are 350 to 325 million years old and are found in the mid-western United States (especially Missouri, Arkansas, and Kentucky). A few Permian species have been found in Russia. During the Carboniferous, the mid-western United States was part of the supercontinent called Pangea and was located just north of the equator. This area was covered by shallow, warm seas.

Some references:

Condra, G.E. and M.K. Elias. 1944. Study and revision of Archimedes (Hall). Geological Society of America Special Paper 53:1–243. This is a classic study. NOT FREE.

Taylor, P.D. and C. Sendio. 2013. Chirality in the Late Paleozoic fenestrate bryozoan Archimedes. Bastalleria 19:41–46. Online for FREE!