Iceland is a North Atlantic oceanic island located between Greenland and northwestern Europe:

Google Earth Satellite image (2015) showing location of Iceland in the North Atlantic Sea.

Iceland has a relatively young geologic origin. It originated about 16 to 3 million years old, when volcanic eruptions began atop a “hot spot” on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, as shown in the figure below.

Ocean-floor topography in relation to Iceland. This map is from The National Geographic Society (1968), Atlantic Ocean Floor Map.

Eruptions continue to present day in Iceland, as the island continues to enlarge. The northern edge of Iceland is situated on the Arctic Circle (60º N). Its waters are classified as boreal (cold) and are located between colder waters to the north and warmer (temperate) waters to the south. It is also important to mention (as is evident from the above figure) that Iceland “sits” on a volcanic plateau that was created by the volcanic flows associated with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This plateau causes Iceland to have a different physiography than that of the surrounding ocean floor. In turn, this plateau could be a “barrier” to the dispersal of the mollusks that crawl about on the adjacent (deeper) ocean floor.

The modern-day seashell fauna of Iceland is generally known but not in great detail. The composition of this fauna is the result of Iceland's transitional-zone geographic and climatic conditions. For example, some of the species found in Iceland also live in Great Britain, France, Norway, and Sweden, whereas other species found in Iceland also live in the arctic circumboreal waters that occur in Greenland, northeast Canada, as well as further south into Maine, Virginia, and North Carolina. Furthermore, some of Iceland’s molluscan species also live in Alaska, and even as far south as northern Japan. It is pertinent (if not alarming) to mention that the arctic circumpolar waters are currently warming at a rate twice that of the global mean temperature (Overland et al., 2017).

Iceland is actually a southern “outpost” of arctic fauna with many arctic species present. Some other arctic species, however, do not reach Iceland. This arctic influence is most apparent along the eastern and northeastern coasts of Iceland.

For most marine bivalves, their dispersal is via free-floating and long-lived planktonic (feeding) veligers. This is the reason why most bivalves can be so widespread, with the main limiting factor controlling their distribution being temperature. Some marine gastropods also have free-swimming veligers—either feeding or nonfeeding---with either a short or long larval life. Some gastropods, especially the carnivorous neogastropods, however have no free-swimming larvae. These factors, taken as a whole, could help explain why some Arctic gastropods are not as widespread as the bivalves.

I was able to obtain a generally good understanding of the taxonomic composition of Iceland’s marine molluscan species, but doing so was not that easy. It took me several days of searching online, as well as looking through a lot of literature, to find even rudimentary data. Seashell books (for seashell collectors) about Iceland’s marine mollusks are essentially confined to a single one: Skeldyrafana Islands, by Oskarsson, I. 1962 [reprinted in 1982] (see image, below). His identifications, which are written in the Icelandic language, however, need considerable revision. He reported approximately 190 species of bivalves and 130 species of gastropods. In addition, he reported numerous “subspecies;” many of which might not even be valid, taxonomically speaking. The book is not available online, but it can be purchased for a reasonable price from online-book dealers.

Cover page of Oskarsson's (1962) book.

My following treatment of Iceland’s marine mollusks is very incomplete and consists of a few commonly occurring species. Nevertheless, the ecologic data that I present here are up-to-date.

A FEW EXAMPLES OF RECENT MARINE MOLLUSKS OF ICELAND

Color images of most of the following species were kindly provided by Lindsey T. Groves, Collections Manager, Los Angeles Museum of Natural History. He obtained these images while on a vacation there in 2016. Exception are a black-and-white image from Oskarsson (1982). and color images of Buccinum undatum. Geographic distribution, environmental data, and depth data are mainly from Coan et al. (2000) or from WoRMS (2023).

BIVALVES

Mytilus eludes

Family Mytilidae

Widespread in the northern Atlantic

A cobble beach, near Hvaines, Iceland, with numerous disarticulated valves of M. edulis.

Two valves of M. edulis collected from the beach fauna near Hvaines.

Chlamys islandica (O.F. Müller, 1776)

Family Pectinidae

Iceland, Greenland, Norway, North Atlantic, Faros British Isles, North Carolina.

Not in Canada nor in Alaska. This is an Atlantic Ocean species.

Note: Early Iceland workers commonly mistakenly assigned this species to genus Pecten.

Arctica islandica (Linnaeus, 1767)

Family Arcticidae

Firm sand, mud, or clay, intertidal to deep (4-480 m)

Iceland, Ireland, Britain, France (Bay of Biscay), Denmark (Faroes Islands), northwestern Russia (Onega Bay, White Sea), Labrador to North Carolina.

Arctica islandica, right-valve.

Spisula solida (Linnaeus, 1758)

Family Mactridae

A burrowing bivalve in sand, uncommonly at low water but mostly sublittoral. Fa

Eastern Atlantic from Iceland, Norway, and south to Portugal and Spain.

Spisula solida.

Serripes groenlandicus (Mohr, 1786)

Family Sardine

Intertidal to about 80 m.

Panarctic and circumboreal = cosmopolitan in arctic and boreal waters:

Iceland, North Atlantic from Greenland to New England; northern Pacific-throughout Bering Sea shelf to Amchitka Island, Aleutian Islands in Alaska, and south to Puget Sound, Washington.

Image of Serripes groenlandicus from Oskarsson (1982).

Mya truncata Linnaeus, 1758

Family Media

Intertidal to 100 m, in mud and sand of protected bays and foreshores.

Circumboreal and panarctic

Iceland, Beaufort Sea to Point Barrow, Alaska, south to Hood Canal and Neah Bay, Washington, and in western Pacific south to northern Japan. Note: this species has a fossil record stemming from Miocene rocks in California (Coan et al., 2021, p. 473).

Mya truncata, left valve.

GASTROPODS

Buccinum undatum Linnaeus, 1758 [has many synonyms]

Family Buccinidae

Predator. Its lavae do not have a planktonic stage; therefore this snail is somewhat restricted in its distributon.

Subtidal dweller. Native to the North Atlantic. It is fished commercially. Specimens are up to 15 cm height.

Iceland and Svalband. West Greenland. Europe (Norway to Spain). Canada: Baffin Island, Queen Elizabeth Islands, Labrador, Newfoundland, Quebec, New Brunswick; USA: Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Virgina (WoRMS, 2023).

Buccinum undatum Linnaeus, 1758, apertural and abapertural views.

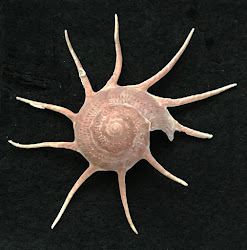

Nucella lapillus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Family Muricidae

Intertidal predator on barnacles (WoRMS, 2023)

Iceland; west Greenland; Canada: Labrador, Quebec, Nova Soctia, New Brunswick; USA: Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York (WoRMS, 2023).

Nucella lapillus (Linnaeus, 1758), apertural view.

References Cited:

Coan, E.V., P.V. Scott, and F.R. Bernard. 2000. Bivalve seashells of western North America: marine bivalve mollusks from Arctic Alaska to Baja California. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Monographs Number 2, Studies in Biodiversity Number 2, 784 pp.

marinespecies.org [=WoRMS.org] 2023

Oskarsson, I. 1982. Skeldyrafana Islands. 351 pp. (in the Icelandic language).

Overland, J.E. et al. 2017. Surface air temperatures. In Arctic Report Card. http://www.artic.noaa.gov/Report Card