Introductory Note 1: Bivalves belonging to family Pectinidae (the pectens) are commercially referred to as scallops.

Introductory Note 2: For some additional images, see my previous post (Nov. 27, 2017) concerning “Colors of Scallops”).

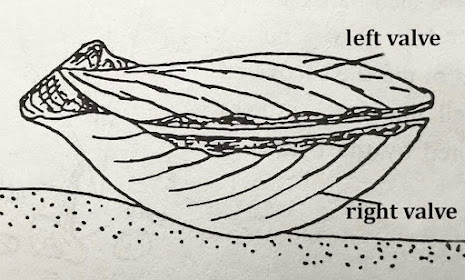

Introductory Note 3: Life position of a pectinid bivalve:

Introductory Note 4: Morphologic parts of a right-valve exterior of a

pectinid valve:

____

Patinopecten caurinus (Gould, 1850)

This species, which is a free swimmer throughout its life, is the largest living scallop in the world. The average size of this bivalve in Alaska is 24 cm in diameter (Foster, 1991). Its valves, which are circular and nearly flat (with small auricles (“wing-like ears”) at the ends of the hinge, have 20 low ribs (Fitch, 1953).

The following information is primarily from <www.sealifebase.ca>

Common Names: “Giant Pacific Sea Scallop” and the “Weathervane Scallop.”

Exterior color: whitish brown; interior color: white.

Geographic Range: Eastern Pacific, from Pribilof Islands, Alaska; Washington; Oregon; and as far south as Point Sur, California (Ignell and Haynes, 2000).

Water Temperature: Temperate (preferred) to boreal.

Depth Range/Habitat: Usually 60–120 m; total range 2–300 m; found in small depressions on sandy-gravelly substrates; free living (unattached).

Maximum Size: Diameter 22.8 cm (Coan et al. (2000, p. 240).

Other Characteristics: Shell is very lightweight and thin.

Fossil Record of the Species: Pliocene (CA) and Pleistocene (CA).

(Top image): right-valve exterior and (bottom image) left-valve exterior of the same Recent specimen of Patinopecten caurinus from Skagway, Alaska. Height 16.5 cm, diameter 17 cm.

Right-valve exterior of a fossil specimen (middle Pleistocene age) of Patinopecten carurinus, Santa Barbara County, Southern California. Height 14.5 cm, diameter 16 cm.

Nodipecten subnodosus (G.B. Sowerby I, 1835)

Common Name: “Giant Lion’s Paw”

Exterior Color: Considerable color variation, from dull purplish-white to brilliant orange and to purplish orange. Interior color: separate bands of purple or white.

For pictures showing color variation, see pectensite.com/Nodipecten%20subnodosus.html

Geographic Range: Pacific coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico [as far north as Guerrero Negro and Cedros Island] and into the Gulf of California [from as far north as Bahia de Los Angeles, Mexico and southward to the southern tip of Baja California] (Smith, 1991). In El Niño years, this species has been detected at Santa Catalina Island in southern California (Coan et al., 2000).

Water Temperature: Warm temperate to subtropical.

Habitat: Low tide to 110 m depth, in small depressions in sand. Absent near river deltas and estuaries.

Maximum Size: Length 21.7 cm (Coan et al., 2000, p. 242).

Other Characteristics: Shell is heavy and thick; 8 to 9 radial ribs, overlain by fine radial riblets; elongate nodes on the ribs are mainly on the main part (= the bulged-out) umbo region of the shell, when viewed from the side.

Fossil Record of the Species: Terrace deposits in Baja California, Mexico––Middle Pliocene and Pleistocene (Smith, 1991, p. 99).

(Top image) right-valve exterior and (bottom image) left-valve exterior of the same Recent specimen of Nodipecten subnodosus From the Gulf of California (exact location unknown), length 14.5 cm, diameter 15.4 cm, thickness (both valves together) 5.5 cm.

References:

Coan, E.V. and P. Valentich-Scott, and F.R. Bernard. 2000. Bivalve seashells of western North America (from Arctic Alaska to Baja California). Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Monographs Number 2, Studies in Biodiversity Number 2, 784 pp.

Fitch, J.E. 1953. Common marine bivalves of California. Bish Bulletin no. 90, State of California Department of Fish and Game Marine Fisheries Branch, 106 pp.

Foster, N.R. 1991. Intertidal bivalves a guide to the common marine bivalves of Alaska. University of Alaska Press, 152 pp.

Ignell, S. and E. Haynes. 2000. Geographic patterns in growth of the giant Pacific sea scallop, Patinopecten caurinus. Fish. Bulletin 98:849–853. [free pdf available online].

pectensite.com/Nodipecten%20subnodosus.html

Smith, J.T. 1991. Cenozoic giant pectinids from California and the Tertiary Caribbean Province: Lyropecten, “Macrochlamis,” Vertipecten, and Nodipecten species. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 1391, 155 pp., 38 pls.

www.sealifebase.ca