In 1876, Cope wrote a brief paper about a single large tarso-metataursus bone that he found in the southwestern United States, in the state of New Mexico. That kind of bone occurs only in the lower leg of birds, as well as in some non-avian dinosaurs. He named his discovery: Diatryma gigantea. In 1916, the first skull of this same large fossil bird was found in the Willwood Formation in the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming. Then, in 1917, the first nearly complete skeleton of this bird was found. Cope realized that all of these fossils represent the same species of flightless bird: namely one that had wings reduced to small stumps, a head as large as that of a modern horse, a large beak with a sizable hook on its end (similar to that found on eagles), and feet with small talons. Most vertebrate paleontologists currently believe that D. gigantea was a fierce predator, but a there are some who believe it was a grazing herbivore that used its sharp beak as a scythe (uwyo.edu/geomuseum/exhibits/diatryma-giganteus.html).

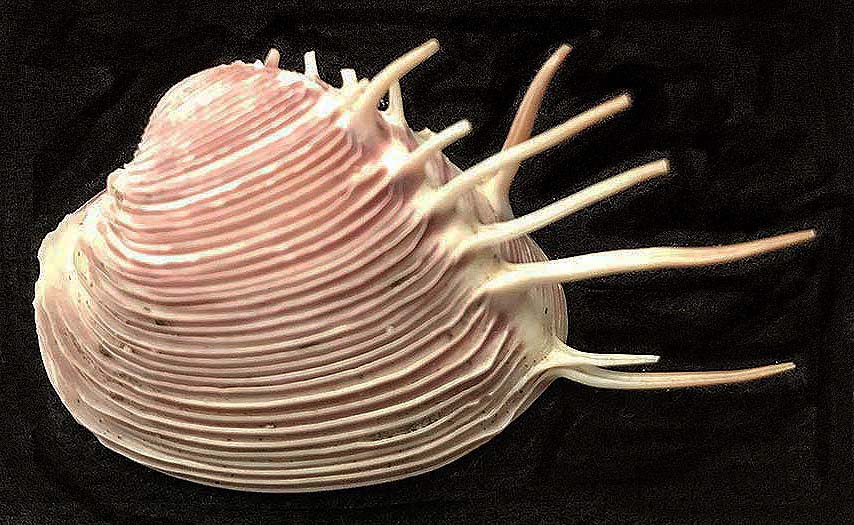

Gastornis gigantea (Cope, 1876) (modified from a figure on p. 498 of Fenton and Fenton, 1958). The adult of this flightless bird was 7 feet tall (2.14 m) and weighed 385 pounds.

In 1884, genus Diatryma was recognized by vertebrate paleontologists as being the junior synonym of genus Gastornis, which up until then had only been found in France (Paris Basin region). It has now been found also in England, Belgium, and Germany (Wikipedia, 2023). According to the international bylaws of taxonomic classification, the name Gastornis is the senior synonym of this animal, thus it has official priority because it was named first. It was not long until paleontologists realized that Gastornis gigantea indeed roamed both the American West (Wyoming, New Mexico, and New Jersey), as well as western Europe during the late Paleocene through middle Eocene times. This interval of time coincided with a worldwide, warm (greenhouse) climate.

According to the very informative account of Gastornis in Wikipedia (2023), there are five to seven species of this extinct genus, including one in the Henan Province of central China. According to Buffetaut (2013), who did a taxonomic update/revision of this sole Chinese species, which is based on a single leg bone of early Eocene age, this particular species should be identified as Gastronis xichuanensis (Hou, 1980).

In 1975, fossil remains of Gastronis were discovered by the paleontologists Mary R. Dawson and Robert M. West doing field work on Ellsemere Island, Canada’s High Arctic area. This fossil occurs in the Margaret Formation of early Eocene age (equivalent to the North American Land Mammal Wasatchian Age). This formation was deposited in a high-latitude area during the worldwide “greenhouse”-time environment, with mild and ice-free temperatures in this particular area. During the winter months, however, it was dark at this locale. The sedimentary rocks containing the fossils were deposited in a coastal-deltaic-plain sediments that grade upsection into a lush lowland-swamp-forest environment. The area is presently at approximately a latitude of 78.4°N in Eureka Sound. Most of the fossils, especially the vertebrate-animal remains are fragmentary and weather worn (Eberle, 2007).

Google-Earth image showing location of the Elsmere Island Eocene fossils and surrounding geographic features.

Fossils found associated with Gastornis include many land plants (e.g., Metasequoia, ginkgo trees, walnut trees) and numerous vertebrates e.g., fish, amphibians, turtles, crocodiles, boa snake, rodents, tapir, brontochere, hyaena, and a few primate-like mammals (Dawson et al. 1976; Eberle and Greenwood, 2012). For a more complete list, see (en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Strathonca Fiord).

All of the known European fossils of Gastronis are of Paleocene age. All the known North American (USA and Canada) fossils are early Eocene age, as is the China occurrence. Most workers are in agreement that Gastronis originated in Europe. Most workers believe also that the most plausible migratory route that Gastornis underwent is the following: it originated during the Paleocene in western Europe; migrated during the early Eocene to both central China and western North America: all of this about 55 to 50 million years ago. This interval coincided with the greenhouse “Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” (PETM) event, which was warmest time interval of the entire Cenozoic (see Groves and Squires, 2023).

The exact route of the paleogeographic distribution of Gastornis out of Europe, however, needs more fossil finds (with precise geologic age dating) in order to resolve exactly how this non-flying bird moved from Europe to North America and China. A very plausible scenario [and shortest route] is the following: Gastrornis migrated during the early Eocene from western Europe into Greenland, then to Ellsmere Island (northern Canda), and then to Wyoming, all via the North Atlantic Land Bridge [NatLB]–De Geer–Thulean land-bridge complex (see map below). Then to complete its migration, Gastornis could have travelled from Wyoming to China during the Eocene, via the Beringia #1 Land Bridge. As a possible alternative to Beringia #1, Gastornis might have migrated from Europe to Asia by an intermittent land connection during the early Eocene.

Paleogeographic map of the northern land masses of the world during the early to middle Eocene (adapted from Brikiatis, 2014—see one of my previous posts about “TERTIARY LAND BRIDGES”, published in November, 2022).

Beard (2002) reported that mammals from the Old World (Europe and Asia) invaded North America at least three times near the Paleocene/Eocene boundary. This boundary is documented best in the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming (this happens to be where most of the North American fossils of Gastornis are found).

Note: Fossil birds similar to Gastornis are the South America phorusrhacids of early late Paleocene through early Pleistocene age, and especially the Miocene (see one of my earlier posts concerning “TERROR BIRDS,” published on November 28, 2021). As mentioned in that blog, only a few of these birds entered southern North America, and not until the late Pliocene via the Panama Canal isthmus (i.e., The GABI event---see one of my previous posts concerning “TERTIARY LAND BRIDGES,” which also includes the GREAT AMERCIAN BIOTIC INTERCHANGE [GABI],” published in November, 2022).

REFERENCES CITED:

Beard, C. 2002. East of Eden at the Paleocene/Eocene boundary. Science v. 295, pp. 47(11):1302–1307. (pdf not free)

Brikiatis, L. 2014. Late Mesozoic North Atlantic land bridges. Earth-Science Reviews 159:47–57. (pdf not free).

Buffetaut, E. 2013. The giant bird Gastornis in Asia: a revision of Zhongyuanus xichuanensis Hon, 1980, from the early Eocene of China. Paleontological Journal

Cope, E.D. 1876. On a gigantic bird from the Eocene of New Mexico. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelpia 28(2):10-11. (free pdf)

Dawson, M.R., R.M. West, W. Langston, Jr., and J.H. Hutchison. 1976. Paleogene terrestrial vertebrates: northernmost occurrence, Ellsemere Island, Canada. Science, v. 192, pp. 781–782.

Eberle, J.J. 2007. Ellesmere Island Eocene fossils. The canadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ellesmere-island-eocene-fossils

Eberle, J.J. and D.R. Greenwood. 2012. Life at the top of the greenhouse Eocene world—a review of the Eocene flora and vertebrate fauna from Canada’s High Arctic. Geological Society of America Bulletin 124:3–23.

Fenton, C.L. and M.A. Fenton. 1958. The fossil book. Doubleday, New York, 740 pp.

Groves, L.T. and R.L. Squires. 2023. Revision of northeast Pacific Paleogene cypraeoidean gastropods including recognition of three new species: implications for paleobiogeographic distribution and faunal turnover. PaleoBios 40(10):1–52. (free pdf).

Hou, L. 1980. New form of the Gastrornithidae from the lower Eocene of the Xichuan, Honan. Vertebrata PalAsiatea 18:111–115.

en.Wikipedia.org Gastornis.

uwyo.edu/geomuseum/exhibits/diatryma-giganteus.html. 2023. Diatryma.