Morocco has great generic diversity of Cambrian and Devonian trilobites, and some have excellent preservation. There are many commercial websites devoted to selling the vast array of specimens. Prices for some of the most spectacular specimens (especially those that are very spinose) can be very expensive! Some of the websites that I visited in preparing this post are listed at then end of my comments. The purpose of this blog post is to provide a brief overview of the types of trilobites found in Morocco.

Google-Earth satellite photo of Morocco and also the general area of the location of some of the spinose trilobites, which are mentioned lastly in this blog post.

My version of the geologic history of trilobites, including

those found in Morocco.

Large trilobites were moderately common during the Cambrian Period in Morocco, whereas spiny trilobites were especially diverse in the Devonian Period. Throughout these geologic times, Morocco was located in the ancient supercontinent called "Gondwana." The maps are based on information found in Scotese (2021).

Dorsal view of a specimen of Aacadoparadoxides briareus?, which is a Middle Cambrian large redlichiid trilobite, about 10 inches in length. Specimens can be up to 15 inches in length. This trilobite is found in Morocco, USA (Alaska, Massachusetts, South Carolina), southeast Canada, South America, Europe, Norway, Poland, and Russia (jurassic-dreams.com).

The specimen illustrated here could be a “fake,” as they are common for this trilobite. Their shells are very thin and subject to breakage during quarrying; thus they usually require some or extensive restorative “cosmetic surgery.” It the price for a large and perfect specimen is only a few hundred dollars, it is likely that it is fake. Nevertheless, it could have great eye-appeal.

Three specimens of the Cambrian trilobite Campropallas teleoso. The largest specimen (upper right-hand corner of image) is 8.5 inches in length and 6 inches wide (image courtesy of Julia and David Denman).The exoskeleton (carapace) of this species is typically very fragile because it is so thin; thus, craftsmen in Morocco have to usually do some repair in order to restore the specimens.

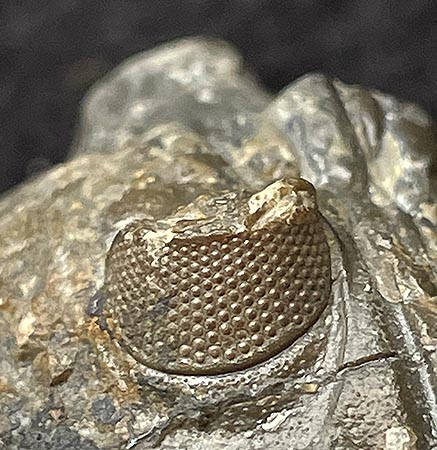

Dorsal view of the exoskeleton (6 cm length and 4 cm width) and also a view of the left (“tower” eye, 0.5 cm tall and 1 cm wide) of the Devonian trilobite Coltrania? oufatensis. The elevated eye (with lenses preserved—which is common in Moroccan trilobites), allowed this animal to be able to see any predators approaching from behind.

Dorsal and left-lateral views of the exoskeleton (6 cm length and 3 cm width) of Devonian trilobite Erbenochile? sp. Its eyes (with the lenses preserved) are elevated. Scratch marks, which were made by the tools of the preparators of Moroccan trilobites, is a “trademark” of many fossils quarried and sold from this region.

Ceratarges is a genus of spiny trilobites. The geologic age of this genus is early to middle Devonian. Its eyes (shown here in brown color) are on long stalks. [Note: well-preserved specimens of this trilobite cost from 600 to 900+ dollars from online fossil dealers]. The sketch of the species shown here, which is based on a figure in Fenton and Fenton,1989, depicts a 4-cm long specimen from Germany. This species is similar to species of this genus found in Morocco. The reason for the many spines is not known, but the spines most likely provided protection from large-sized Devonian predatory fishes (arthrodire placoderms). I shall soon post a blog about these fish, so "stay-tuned!"

References Consulted:

Fenton, C.L. and M.A. Fenton. 1989. The fossil book. A record of prehistoric life. Doubleday, New York, 740 pp.

Scotese, C. R. 2021. An atlas of Phanerozoic paleogeographic maps: the seas come in and the seas go out. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

Some useful websites (that have many images of trilobites):

jurassic-dreams.com/products [nice images and good information about Acadoparadoxides]

Trilobites.life/Moroccan-trilobites

Fossilicious.com/trilobites-of-morocco

Fossilera.com/fossils-for-sale/trilobites [many images!]

amnh.org/research/paleontology/collections/fossil-invertebrae-collection/trilobite

this site illustrates Devonian trilobites of the United States (genera in alphabetized order)