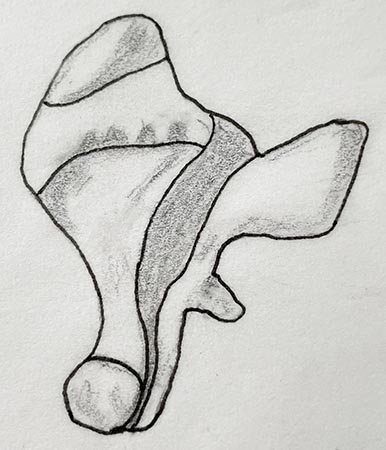

Pyktes: An Unsual-Looking Late Cretaceous Gastropod

Popenoe (1983) discovered, named, and illustrated the aporrhaid-gastropod genus Pyktes triphyllon, which has a very distinctive shape because it has two unusual-looking lateral projections of its shell. These lateral projections resemble boxing gloves, hence the derivation of the generic name–Pyktes, which is Greek, for a boxer or pugilist. This species, which is of middle Late Cretaceous age (i.e., late Santonian Stage) is found on the east side of Sacramento Valley, northern California. This gastropod was probably a shallow water, normal-marine, sandy bottom dweller.

Tracings made by me of two views of Popenoe’s photographs of the holotype (= the primary specimen used used by Popenoe (1983) to define his Pyktes: apertural (front) and abapertural (back) views, in successive order. The holotype has a height of 29.3 mm.

According to Popenoe (1983), the genus Pyktes is found also in younger Cretaceous rocks elsewhere in northern California and in the Rocky Mountains. According to Kiel and Bandel (1999), Pyktes occurs also in Late Cretaceous (Santonian Stage) rocks in South Africa.

References

Kiel, S. and K. Bandel. 1999. The Pugnellidae, a new stromboidean family (Gastropod) from the Upper Cretaceous. Palaontologische Zeitschrift 73 (1/2):47–58.

Popenoe, W.P. 1983. Cretaceous Aporrhaidae from California: Aporrhainae and Arrhoginae. Journal of Paleontolgy 57(4)742–765.