The bivalve (clam) Spondylus is a favorite among seashell enthusiasts, who like these clams because of their picturesque shape, potentially vivid colors, and, in some species, long spines. The shells of many specimens, however, can be obscured because of attached corals and other sea life. Spondylus is indicative of warm (tropical to subtropical) seas, and the geologic record of this genus ranges from the Jurassic Period to Recent times. Its distribution today is pantropical, with about 40 or so species. The number is inexact because of the notoriously high degree of variability in the shape and features of the shells.

Spondylus has been referred to as the “thorny oyster” or the “spiny oyster,” but it is not an oyster. Some species can resemble the bivalve Lima. In terms of the development of its hinge morphology, however, Spondylus has some degree of affinity with Pecten clams (scallops). Spondylus can be thorny or spiny, and you have to be very careful when handling it. The spines, whether short or long, can be very sharp. It might be necessary to wear thick leather gloves when handling some of the specimens.

The following images are of a representative Recent species of Spondylus, namely S. varians Sowerby, 1838 from low-energy, tropical shallow waters of Thailand. Like all bivalves, Spondylus consists of two valves. The right valve (so-called "lower" valve) is attached to rocks, corals, or other hard substrate. As a result, the right valve can have an extremely variable shape because it resembles the shape to which it is attached. The left valve (so-called "upper" valve) is free, and its shape can be determined by the degree of water energy (e.g., quiet water versus rough water). Quiet-water Spondylus species have longer spines that the rough-water ones. As seen below, the right valve (lower valve) of a specimen of S. varians extends 120 mm, when viewed from left to right, and the left valve (upper valve) is 80 mm when viewed from top to bottom.

both valves (side views): upper valve flat, lower valve cup shaped

upper valve exterior

upper valve interior

lower valve interior

Like all specimens of Spondylus, the right (attached) lower valve of S. varians has a thin dark ligament between two stout teeth (crural teeth). The left (free) valve has two corresponding sockets to accommodate these teeth.

In the images shown below are the presently known four species of fossil Spondylus from the west coast of North America, from Late Cretaceous through Eocene age. The diagram shown here is a summary of their geologic history in this area. As you can see, Spondylus occurred only during warm times.

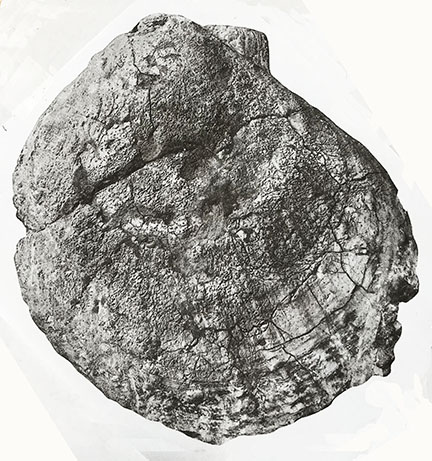

The oldest Cretaceous species from this region is Spondylus rugosus Packard, 1922 from southern California. Preservation is commonly very poor. Specimens can be large, up to 95 mm height. The specimen illustrated here is the left valve of the holotype [= the specimen found by Packard and used by him to name the species], height 95 mm, width 72 mm, Santa Ana Mountains, southern California.

The next geologically younger Late Cretaceous species is Spondylus subnodosa (Packard, 1922) from northern and southern California and possibly Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Preservation is generally good. Specimens can be quite large, up to 150 mm height. \The specimen illustrated here of S. subnodosa is the right valve of the holotype, height 150 mm height, 140 mm width, Santa Sana Mountains, southern California.

The next geologically younger species of Spondylus known from the west coast of North America is of early Eocene age (about 52 million years ago) and is Spondylus batequensis Squires and Demetrion, 1990 from Baja California Sur, Mexico. The specimen illustrated here is the right valve of the holotype, height 21 mm.

NOTE: There has been confusion regarding the name and the morphologic characteristics of subnodusus because Packard (1922) described it as both Lima subnodosa Packard, 1922, p. 421 and as Spondylus striatus Packard, 1922, p. 422. This bivalve actually is a Spondylus and not a Lima. Furthermore, because subnodosa was described one page before striatus was described, subnodosa is the official name of this species.

During the middle Eocene (about 45 million years ago) on the west coast of North America, Spondylus carlosensis Anderson, 1905) was present in southern and central California. Another possible species is Spondylus cliffensis M.A. Hanna in the San Diego area, but it is likely a synonym of S. carlosensis.

At the end of the middle Eocene and the beginning of the late Eocene, about 37 million years ago, global cooling created a turnover event, which strongly affected the warm-water, shallow-marine bivalves and gastropods of the west coast of North America. They began to decline in numbers and many were eventually replaced by cooler water genera and species.

No comments:

Post a Comment