Brachiopods belong to phylum Brachiopoda. They have a long geologic history, stemming from the Cambrian Period and ranging into modern times. They were the most diverse during the Paleozoic, where as today, they are a relatively minor group of invertebrates, found mostly in intermediate to deep depths in the ocean.

There are two classes within phylum Brachiopoda: Class Inarticulata (Cambrian to Holocene = recent) and Class Articulata (Cambrian to Holocene). In the inarticulates, the two valves are weakly held together by muscles. In the articulates, the two valves are united along a hinge line by means of teeth and sockets, which help to securely hold the valves together (even after death of the animal), thereby greatly increasing the chances of articulates to be fossilized.

Inarticulates are represented mostly by lingulids, which are burrowers. These are found most commonly in black muds laid down in poorly oxygenated brackish intertidal and lagoonal waters in tropical and subtropical shallow-marine areas. Astonishingly, in this setting, which is ill-suited for most marine invertebrates, lingulid brachiopods have lived with virtually no change in their external form, from the Cambrian to modern day.

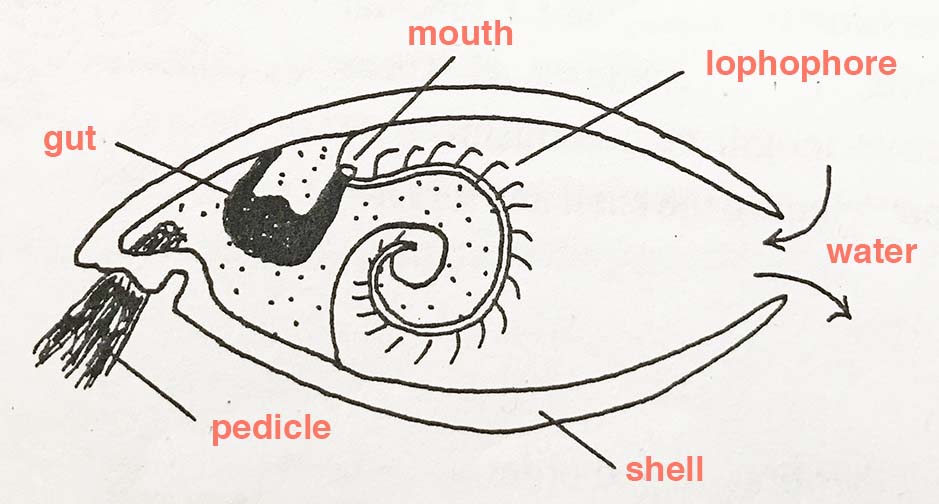

Side view of the living position of a lingulid brachiopod in its burrow. The lophophore is a soft organ consisting of ciliated and coiled tentacles (brachia) whose function is to circulate water, distribute oxygen, and remove carbon dioxide. Water currents generated by the cilia move food particles toward the mouth. Note: The name “brachiopod” (brachio, arm; pod, foot) refers to the brachia of the lophophore, which were assumed wrongly by early workers to function for locomotion purposes.

The fleshy stalk (pedicle), by which the lingulid attaches itself to the floor of its burrow, is much longer than the brachiopod shell. Lingula anatina lives in a vertical position in its burrow, with the pedicle extending into the mud/sand with the upper edges of the two calcium-phosphate valves (shells) situated just below the ocean-floor surface. The burrow can be as deep as 30 cm. At low tide, or when disturbed, the animal withdraws itself down its burrow by contracting its pedicle. This particular brachiopod lives today mainly in Japan at depths from the tidal zone to about 42 m (138 ft.) (Wikipedia, 2023). It is common in coastal mudflats and can survive for a short period of time in tidal water made brackish by river-flood waters.

Exterior view of both the left and right valves of a modern-day specimen of Lingula anatina Lamarck, 1801. These disarticulated valves are 3.5 cm long and 1.6 cm wide and is from Queensland, Australia.

Interior view of the preceding valves of L. anatina. Specimen is 40 mm long and 38.5 mm wide.

Side view of the exterior of a specimen of an articulate brachiopod. The slightly larger valve (pedicle valve) has a pedicle opening (called the foramen) through which a short, leathery pedicle extends and attaches to the substrate (e.g., pebbles). The two valves, which consist of calcite, are biconvex and resemble an ancient Roman oil lamp, hence, the common name “lamp shells” for articulate brachiopods. The valves are strongly held together by teeth and sockets (i.e., the valves are articulated together; hence the name: “articulate brachiopods.”

Exterior views of a modern-day specimen of the articulate brachiopod Laqueus californicus (Koch, 1848). This specimen is 40 mm long and 38.5 mm wide. Notice the pedicle, which extends out from the inside of the pedicle valve.

Interior views of the preceding specimen of the extant (living) articulate brachiopod Laqueus californicus dredged from 40–50 fathoms depth off Catalina Island, southern California. The loop-shaped calcareous ribbon (brachidium) provides support for the lophophore. The markings on the inside of the valve bearing the pedicle are called the pallial markings; they were formed by fluid-filled passageways of the fleshy body-well.

No comments:

Post a Comment