Maclurites is restricted to Ordovician time, thus it is a guide [or index] fossil for the Ordovician Period. This genus belongs to family Macluritidae, which includes 10 genera.

Maclurites has a type of shell coiling called hyperstrophic, in which the animal is anatomically dextral (its genitalia are on right), but its shell is falsely sinistral, being actually ultradextral. If there is an associated operculum (the lid-like, partial or complete covering of the aperture), the operculum exhibits counter-clockwise coiling.

Most gastropods have dextral (right hand) clockwise coiling of the shell, and any associated operculum exhibits counter-clockwise coiling (see image immediately below). A few gastropods are mirror opposites and have sinistral (left hand) counter-clockwise coiling of the shell, and any associated operculum exhibits clockwise coiling.

In my Nov. 20, 2014 post, entitled "Gastropod operculum," I provided views of the dextrally coiled, gastropod shell Megastrea undosa. In this present post, I provide another view of the exterior side of its operculum (38.7 mm hight), which shows counter-clockwise coiling.

Although hyperstrophy is best determined using soft parts for anatomical study, in the case of extinct gastropods, like Maclurites, molluscan paleontologists have to rely on the coiling direction of its calcareous operculum. As shown below, the operculum of Maclurites is coiled counter-clockwise, thus it cannot be a sinistral gastropod.

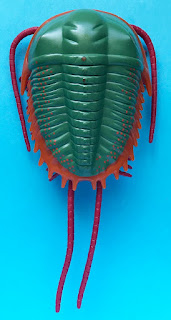

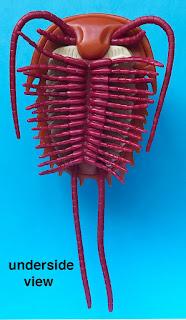

The following four views are of a specimen of Maclurites sp. [68.4 mm diameter, 21 mm height] from the Lower Ordovician Lebanon Limestone, near Nolensville, Tennessee.

front or apertural view, aperture (poorly preserved) is to the right

back or abapertural view

basal view

dorsal view (the "tip" is missing)

The shell rested on its very flat base, which provided great stability for the shell, thereby resisting being flipped over by waves or currents. The flatness of one side of the shell is inferred to be related to its sessile (unmoving), filter-feeding mode of life.