Hundreds of published articles have depicted the classic treatment of horse evolution as shown in the image below: a gradual linear evolution showing the earliest horses changing, over time, into larger size, fewer toes, and larger teeth.

from en.wikipedia.org (2019), under the title of "Horse evolution"

Modern studies show that the earliest horses should be referred to, however, as "horses" (in quote marks). Some researchers maintain, furthermore, that only the very modern horse, Equus, is a true horse. Most modern researchers maintain that the evolution of the horse was contrary to the diagram shown above, and definitely not linear nor gradual.

The name Hyracotherium Owen, 1841, which has been long been traditionally regarded as the earliest horse, is now known to be a too all-encompassing name, because the earliest "horses" were comprised of several genera, not just one genus (Froehlich, 2002--see reference at the end of this post). Hyracotherium is still a valid genus name, but it applies today only to rare specimens of early Eocene "horses" (evolutionarily speaking, very primitive and, thus, the basal group of subsequent horse-like animals) found near London and Paris. The early Eocene "horses" known from western North America [Wyoming, northwestern New Mexico, and to a lesser degree in Colorado] belong to at least five genera (some of which are morphologically very similar to each other), and one is Eohippus Marsh, 1876.

What is somewhat confusing is that, originally, the western North American earliest "horse" remains were identified as belonging in genus Eohippus, later changed to Hyracotherium, and are now reassigned to Eohippus.

Eohippus was small-dog size. It had four toes on its front legs and three toes on the rear legs. Eohippus lived during the early and middle Eocene epochs (55 to 40 million years ago).

An entire skeleton (about 12 inches high at the shoulder) of Eohippus angustidens (Cope, 1875) of Eocene age from Wyoming. This specimen is still on display at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM). By permission of LACM, it was photographed R. Squires and used in a published article by Squires and Squires (1981).

Eohippus angustidens is found in lower Eocene (Ypresian Stage) strata in Wyoming, northwestern New Mexico, Colorado, and tentatively from Baja California, Mexico.

The image on the left is the side view of a single molar tooth (a cheek tooth), 6.5 mm height and 10 mm length, of Eohippus angustidens (Cope, 1875) from Eocene rock in Wyoming. The image on the right is the top view of the same molar tooth. The fact that the molar teeth (cheek teeth) of Eohippus has low crowns indicates that the animal was a browser that fed on fruit, leaves, and twigs, rather than grasses.

Compared to geologically younger horses, including the modern horse Equus caballus, Eohippus was much smaller with shorter legs, more toes per foot, and had a much smaller skull with smaller teeth. Shown above is the comparative size of a molar tooth of Eohippus versus that of a corresponding molar tooth (partial specimen [52 mm height] because the lower part is missing) of the modern-day horse Equus caballus.

This image is the top view of the same molar tooth (24.3 mm width) of the modern-day horse shown above. There has been, however, some differential weathering of the top surface. The molar teeth of Equus caballus are broad and relatively flat for the purposes of crushing and grinding grass. The teeth of E. caballus are called hyposodont teeth because they possess thick tough layers folded down into the main structure of the tooth. These kind of teeth allowed horses more modern than Eohippus to graze on silica-rich grasses.

Treating the geologic history of "horses," including their migrations among the continents is beyond the scope of this post. For an excellent and succinct animation depicting this history, Google:

netnebraska.org

Froehlich, D.J. 2002. Quo vadis eohippus? The systematics and taxonomy of the early Eocene equids (Perissodactyla). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 134:141-256. [available online as a free PDF].

Squires, J. and R. Squires. 1981. Can you name the first horse? Equus 40:52-53, 58.

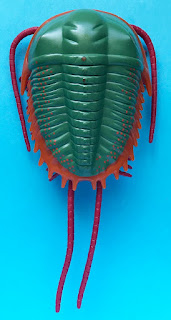

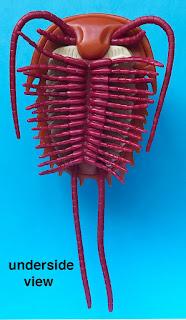

Some trilobites are found enrolled. That is to say, their mineralized exoskeletons rolled up (partially or completely), much like modern pill bugs do. Enrollment was the way for

Some trilobites are found enrolled. That is to say, their mineralized exoskeletons rolled up (partially or completely), much like modern pill bugs do. Enrollment was the way for