Fusulinids are much larger than most foraminifera, which are extinct single-cell protists that consisted of an amoeba-like organism surrounded by a cylindrical/tubular calcareous shell (test = exoskeleton). Most fusulinids, which are between 5 and 20 mm in length and shaped like grains of rice, are of Late Paleozoic (Carboniferous (Late Mississippian) and Permian) age. They show rapid evolutionary development during the Permian. They were bottom-dwelling (benthic) organisms that chiefly lived in warm-water, shallow-marine offshore environments. Their calcareous remains (tests) are commonly major components of limestone. They did not inhabit brackish water nearshore or high-saline embayment environments. Fusulinids have been used extensively by oil companies for determining geologic ages of strata cored during oil-well drilling.

A hand specimen (19 cm wide and 80 cm high) of calcareous (limy) siltstone containing many specimens of fusulinids of Permian age from the Guadalupe Mountains in southeastern New Mexico. The largest specimen (20 mm length) is on the upper middle right side of the rock.

Numerous specimens (about 100) of Fusulina sp. tests weathered out of their enclosing rock matrix. The largest ones are 10 mm in length. These specimens are of Middle Pennsylvanian in age and from shale rock in the Hueco Mountains, near El Paso, Texas.

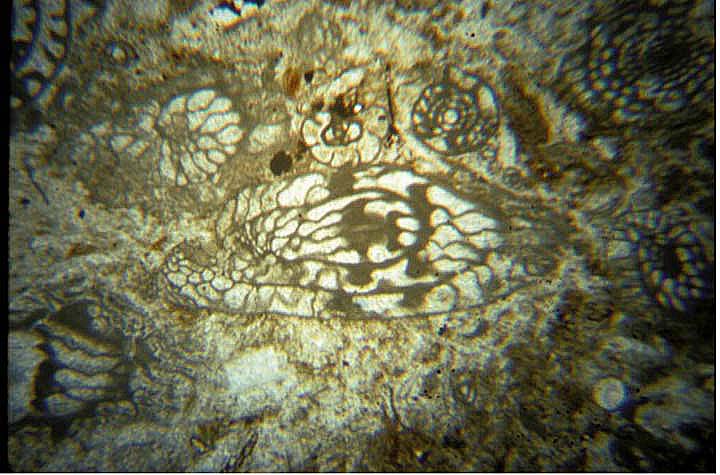

Because the tests of the approximately 50 known genera of fusulinids can be externally very similar looking, it is necessary to cut thin sections of their tests in order to microscopically examine their distinctive internal structures and thus determine their genus and species. A longitudinal section (axial) and a cross section (sagittal) are illustrated in the following sketch shown below.

Axial and sagittal cross-section views.

The center of this photomicrograph (taken via a microscope) shows an axial view of a fusulinid test in a thin-section of rock. In the background are some sagittal views of nearby specimens.