“Shipworms” are not “ships” nor “worms.” They have also been called “pile worms,” in reference to their presence in wooden piles (logs) that hold up piers. These so-called "worms" are actually highly derived bivalve mollusks that bore wood.

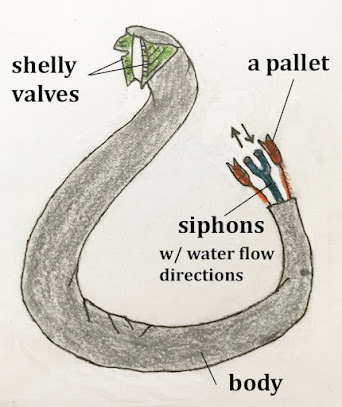

Sketch of the soft body, shell valves, and pallets of a living specimen of Teredo missing its woody enclosure. The thin calcareous shell is also missing.

"Shipworms" can bore soft wood at the rare of four inches per month. Even the hardest woods are no match for them. They actually eat the wood (driftwood, pier legs, bottoms of boats), and that is how they get their nutrients. Even though these bivalves are small in size, a colony of them can literally destroy wood. They bore (drill) along the grain of wood and created long holes. Eventually, the wood is riddled with holes and falls apart. Their actions are similar to termites, hence they have been referred to as “termites of the sea.”

“Shipworms” have wide dispersal in oceans but are primarily shallow-marine/intertidal dwellers. This wide dispersal is because their larvae are free swimming. Based on exceptionally well preserved silicified remains in France, the fossil record of “shipworms” extends back with certainty to the Middle Cretaceous (Cenomanian Stage) (Robin et al., 2018). On the west of North America, I have found teredinid? calcareous tubes in Paleocene and Eocene shallow-marine driftwood, but in actuality, they might fossils of annelids (worms) or other marine animals.

Although “shipworms” are generally small in size, there is one group belonging to genus Kuphus whose calcareous tube can up to 61 inches long (approx. five feet). (See my earlier blog post of Sept. 29, 2020, entitled Kuphus giant bivalve tube) about this curious animal. You have to see it with your own eyes to see how large they can get.

“Shipworms” are commonly skipped over in most popular books on shell collecting and identification because their shells are not pretty nor spectacular looking.

Scientifically speaking, “shipworms” and their earlier cousins belong to the family Teredinidae Rafinesque, 1916. Shown below is the anatomy of genus Teredo, one of the most common of the teredinids, is representative of a typical “shipworm.” Another common genus is Bankia.

Teredinids consist of a long, fragile wormlike tubular body. The bored wood protects the tubular body, which can be encased in its bored tunnel by a thin layer of white calcareous carbonate (aragonite) secreted by the bivalve’s mantle. At the anterior end or drilling end of the animal is a pair of sharp-edged valves [referred to as left and right valves] consisting of calcium carbonate that actually form the “drill” that bores into wood, and these two valves fit together and form a rounded shape.

Sketches of Teredo left valve: external and internal views (from Turner, 1966, p. 135, G, figs. 1, 2).

At the opposite (open) end (= the siphon end) of the tubular body are paired structures (either simple or complex) called pallets. These are specialized organs located at the base of the siphons and function to close the burrows when the siphons are withdrawn. The siphons regulate water flow in-and-out of the tubular body part of the animal and help seal the tube from predation or dessication (Turner, 1966).

For proper identification as to genus of a teredinid requires the study of its pallets, which are small and delicate. They are not easily preserved, thus in the case of fossil teredinids, certain generic identication is usually not possible. Two commonly occurring genera are Teredo Linnaeus 1758, and Bankia J.E. Gray, 1842. They can look very similar, but there pallets are very different in shape.

As shown below, the pallet of a Teredo has a single-paddle shape (typically 2 mm long). The pallets of Bankia are much larger and have a distinctive conical “cone-in-cone” shape consisting of numerous cones, with the total length of the structure about 7 mm. Their tubular bodies otherwise can look very similar.

Teredo pallet: 2 mm long; from Carlsbad, California.

Bankia pallets: longest one is 20 mm; these are from Carlsbad, California.

I am including this last paragraph for readers who have wooden-hulled boats docked in marine harbors (note: shipworms cannot survive in fresh water). In tropical seas, shipworms multiply so fast that the life of an untreated wood plank or board may be little more than six months! They can “honeycomb” a solid piece of wood in 15 weeks. Shipworms can release into the water a total of 100,000,000 free-swimming eggs in one year; thus the infestation by these borers may spread quickly. The two paired smalll shells that lie alongside the head of the shipworm are every effective as raspers. Creosote impregnations is the most effective protection against shipworms. Boat that spend most of their time at sea are less liable to damage than those stored in a harbor. This is because fast-flowing water inhibits the borers from settling (Smith, 1956).

Cited Literature:

Robin, N. and nine other authors. 2018. The oldest shipworms (Bivalvia, Pholadoidea, Teredinidae) preserved with soft parts (western France): insights into the fossil record and evolution of Pholadoidea. Palaeontology 61 (no. 6):905–918.

Smith, F.G.W. 1956. Shipworms, saboteurs of the sea. National Geographic 60(14):559–566.

Turner, R.D. 1966. A survey and illustrated catalogue of the Teredinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Museum of Comparative Zoology, 265 pp., 64 pls.

No comments:

Post a Comment